Not sure about you, but I wonder about this a lot when I need to onboard new colleagues, colleagues who were writing mostly SQL only till the day before.

This post is for people who needs to start writing data pipelines (or DAGs) for Apache Airflow, know already how process their data, but have little or none knowledge of Python.

This post will not tell you how to install Airflow on your machine, this quick start guide will, but check with your colleagues how you do thing in your organization. My assumption is that you work in an environment where Airflow is already used in production and you don’t need to worry about that. If this is not the case, you will need something more than this post.

I hope that after reading this you will be able to understand the code written by your colleagues and feel confident enough to start writing your own DAGs.

I will try to keep this as much practical as possible, as if you should work with me. I assume you know nothing about Python, feel free to skip the sections you are familiar with. Also feel free to ask questions, I am always up for a chat.

Boring things

I will write another post about the building blocks of Airflow, for now let me just share these:

- a DAG is an ETL process (for now 1 DAG == 1 file)

- a DAG is made of multiple Tasks

- a Task is an instance of an Operator

- an Operator does things (moves data, sends emails, writes a post on dev.to)

If you need to know what DAG stands for, just click the hearth icon and I will tell you.

A Basic DAG

from datetime import datetime

from airflow.models import DAG

from airflow.operators.dummy_operator import DummyOperator

my_dag = DAG(dag_id="sample_dag",

start_date=datetime(2020, 4, 29),

schedule_interval="0 0 * * *"

)

start = DummyOperator(dag=my_dag,

task_id="start"

)

end = DummyOperator(dag=my_dag,

task_id="end"

)

start >> end

At the end of this post you should be able to recognize that this DAG runs every day at midnight and does more or less nothing.

But let’s try to read it line by line.

Imports

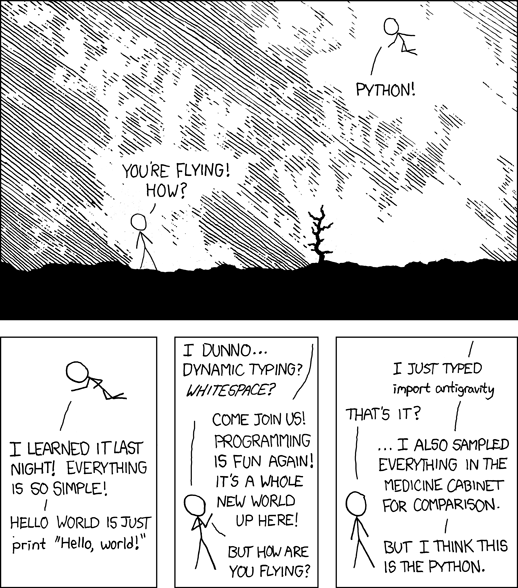

Python can do a lot of things, but to save resources not everything is available all the time. What needs to be loaded in the computer memory is left to the developers.

When you want to use something that is not part of the basic Python, you can import the needed Python module or library.

import antigravity

Now if I want to use a method of antigravity I need to call it using the module name: antigravity.fly()

If the module name is too long, you can use an alias:

import antigravity as ag

ag.fly()

Widely used modules have standardized aliases (but this is another story).

Some modules are quite big and it is possible to import only part of them.

from datetime import datetime

from airflow.models import DAG

from airflow.operators.dummy_operator import DummyOperator

This allows us to avoid the module name (see below).

Not all modules are installed on your machine when you install Python, you can install more module using a tool like pip.

Defining the DAG

my_dag = DAG(dag_id="sample_dag",

start_date=datetime(2020, 4, 29),

schedule_interval="0 0 * * *"

)

This will create our DAG, which Python will store in the variable my_dag that we will use later on.

This DAG will be picked up by the Airflow scheduler and executed depending on its schedule_interval and start_date. The dag_id is the identifier used internally by Airflow, you cannot have another DAG with the same name.

A DAG is created using the arguments we pass to its constructor (DAG()), if this is the first time you pass arguments to a Python method let me highlight a few things:

- we pass three arguments with the format

param_name=value - we pass three arguments to this DAG, but the DAG class accepts more of them, the missing one are filled with default values. You can the full list of parameters here

dag_idis actually the only mandatory parameter. As you probably guessed mandatory parameters have no default and must be passed every time you call a function- the format

param_name=valueis not necessary, but allows us to pass values in the order we prefer. Using names allows us to pass only the needed parameters and we are not forced to change our code if the function we use adds more optional parameters.

For this reason you could remove dag_id=, invert the named arguments, and the code will still work:

my_dag = DAG("sample_dag",

schedule_interval="0 0 * * *"

start_date=datetime(2020, 4, 29)

)

While this…

my_dag = DAG("sample_dag",

"0 0 * * *"

datetime(2020, 4, 29)

)

…makes me to open the link above to see what really are the second and third parameters of the DAG constructor.

Additional notes:

datetime(2020, 4, 29)returns the 29th of April 2019 in a format understandable for the DAG method- the

schedule_intervaluses a format called crontab expression. This DAG will run every day at midnight. You can learn more about crontab expression using something like crontab.guru (or clicking the Unicorn, so I will write a post about crontab expression for you) - technically speaking we are creating an instance of the DAG class (but I will not write a post about this and you should feel bad about thinking that a click will make me your object oriented writer)

At this point we are ready to add tasks to our DAG.

Tasks

start = DummyOperator(dag=my_dag,

task_id="start"

)

end = DummyOperator(dag=my_dag,

task_id="end"

)

start >> end

Task definition looks similar to the DAG definition. Here we are using a very important Airflow operator: the DummyOperator which does absolutely nothing, but allows us to focus on other things:

- a Task needs a unique

task_id task_idis mandatory, it is my convention to keep it named- remember the DAG variable? A Task needs to know its parent DAG, so we use that variable here:

dag=my_dag

Finally we have the line

start >> end

If you guessed that it means the start execution is followed by the end execution you have guessed right. We can also write it as end << start, but of course it is less immediate.

>> and << are called bitshift operator (you can use this new knowledge as icebreaker at the next meetup).

In case you are reading some old Airflow DAGs, you could find this ancient syntax (but we modern people are better off sticking to the bitshift operators):

start.set_downstream(end)

Check questions

If you scroll up you should now be able to understand what this DAG is doing.

Here some questions to check if you got everything right:

- From which module do we import

DummyOperator? - In the DAG definition can I replace

start_date=datetime(2020, 4, 29),withstart_date=datetime.datetime(2020, 4, 29),? - Because the DummyOperator does nothing, will the task

startandendrun together? - My unbirthday this year is on the 7th of May 2020, will this DAG run that day?

- Will the two task definitions work?

start = DummyOperator(my_dag, "start" )

start = DummyOperator(dag_id=my_dag,

"start"

)

Conclusions

At this point you should be familiar with Python concepts like imports and how to call methods with more or less arguments. You should have also a general idea about the relationship between Airflow DAGs and Tasks, and how to create dependencies between Tasks.

In the next episode we will focus on some fundamental Python data structures that can make our DAGs’ code simpler and easier to maintain, some less-dummy operators and other nice things. Till then stay… scheduled.

Categories: Airflow, , Python